History

The former Police Administration Building has a long and complicated history. Any repurposing of the Roundhouse must contend with this legacy. The building was conceived by Richardson Dilworth, one of the most forward-thinking and progressive mayors in Philadelphia history. Over time, the building became tainted by its associations with destructive urban renewal initiatives of the 1960s and ‘70s, and police brutality. However, there are several examples of buildings with dark pasts that have been transformed into part of the solution, repairing historic wrongs while maintaining the important buildings themselves.

Progressive origins

Philadelphians elected the city’s first progressive administration in 1952, with Joseph Clark as mayor and Richardson Dilworth as District Attorney. Dilworth launched a reform of the district attorney’s office by professionalizing the staff, rooting out political influence and corruption, promoting civil rights, and ending discriminatory treatment of Blacks and other minorities.

Elected mayor in 1958, Dilworth set out to modernize municipal services. His administration commissioned the design and construction of the Municipal Services Building in Center City, allowing cramped city offices to move out of City Hall into a modern, efficient building with sufficient space for growing city services. The building itself was intended to symbolize a modern, progressive city administration servicing the needs of Philadelphia residents.

Mayor Dilworth set his sights on modernizing and reforming the police department, just as he had modernized municipal services and the district attorney’s office. First, he sought a modern, efficient, central police headquarters as an alternative to the increasingly inadequate police headquarters long housed in the basement of City Hall. The new building would accommodate the police commissioner, administrative offices, a central communications center, detectives’ offices, forensic laboratories, records storage and management, a small arraignment courtroom, an auditorium, jail cells for short-term use, a cafeteria, and a public lobby for public information and exhibits.

Second, Dilworth wanted a police headquarters that would both create and symbolize transparency and openness in policing, and break up the cronyism between the police and politicians in City Hall. Instead, the new police headquarters would be open to journalists, the public, lawyers, and citizen advocacy groups. These objectives led to a design that included a welcoming front plaza facing Franklin Square, an open and transparent ground floor, a central public lobby and elevator core, and a cafeteria open to the public. Quite simply, Dilworth wanted to let the light shine in.

An architecture of democracy, transparency, and openness

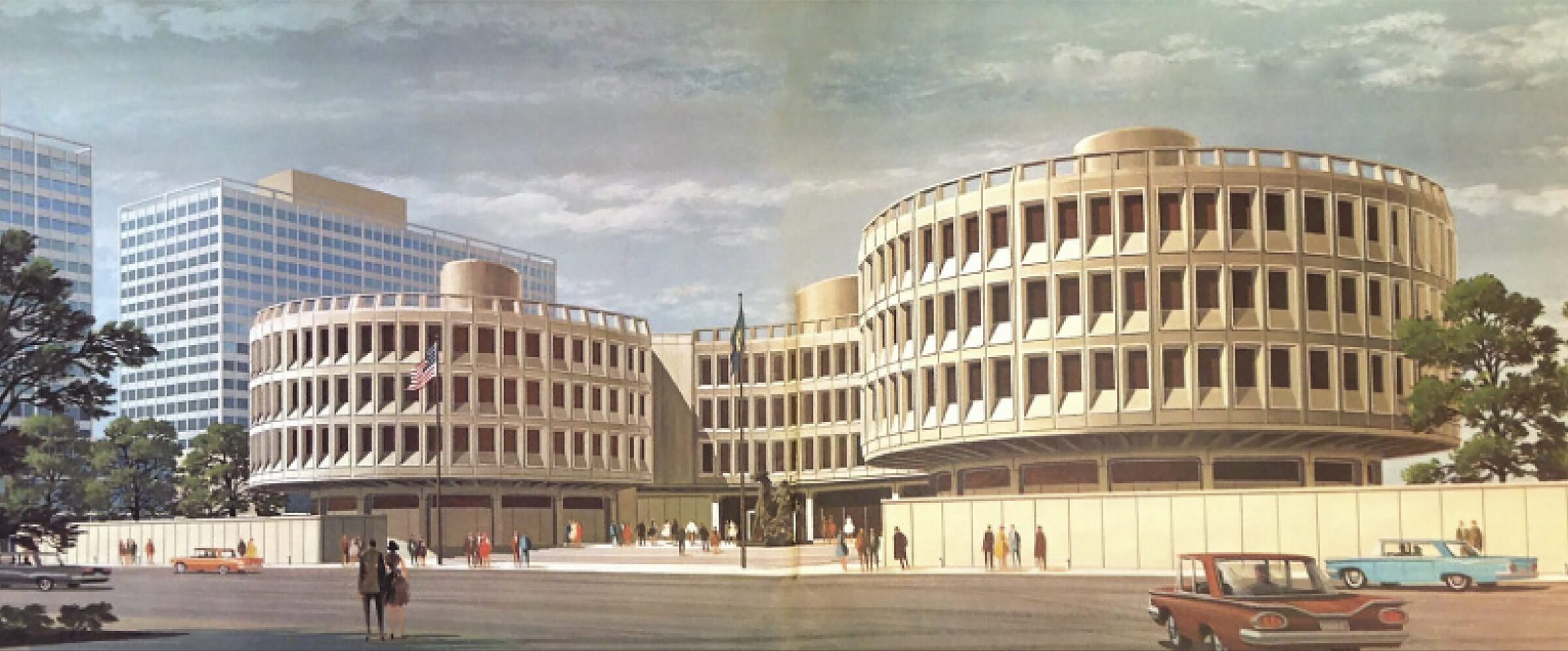

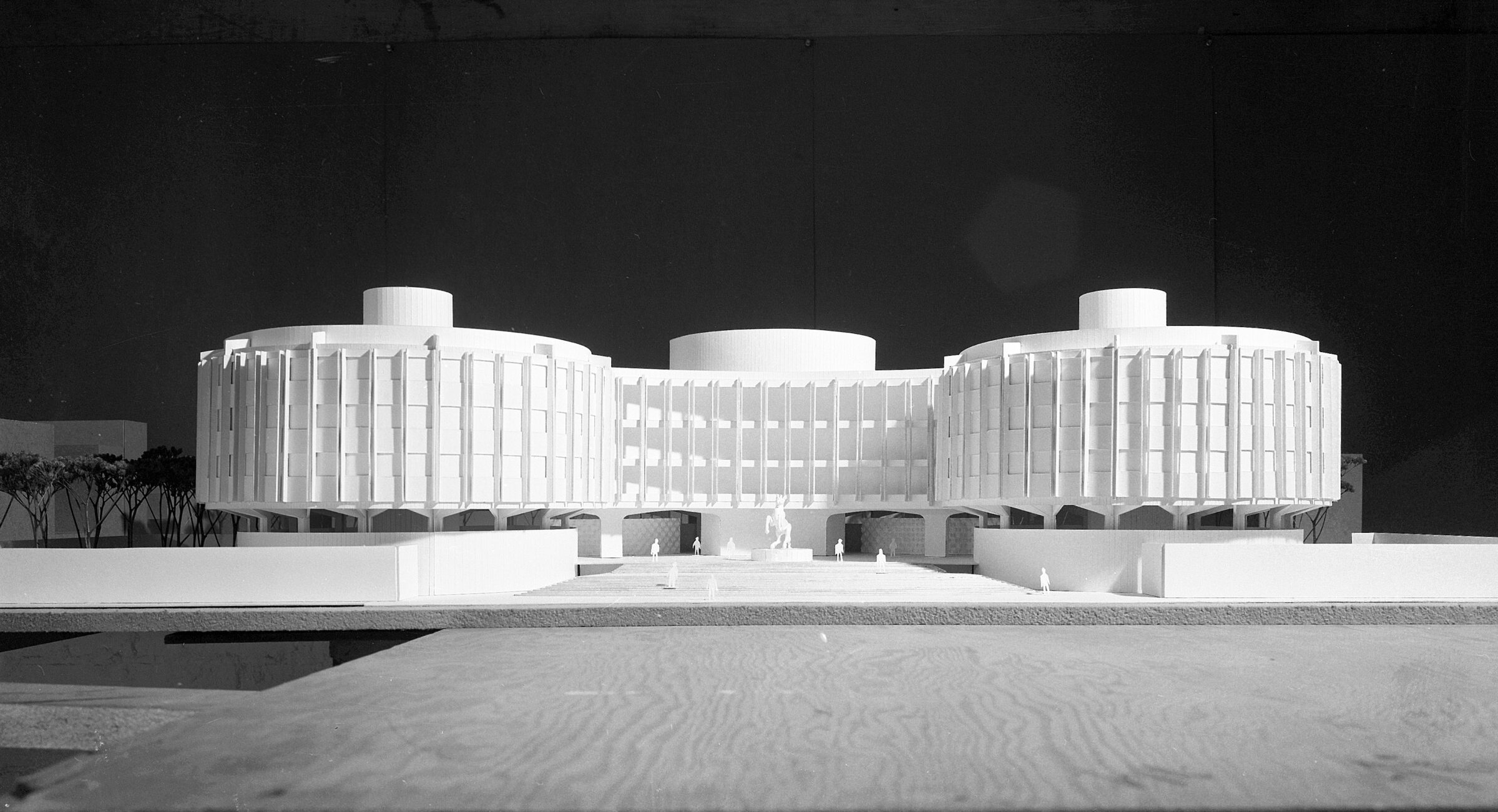

In 1959, Philadelphia commissioned the eminent Philadelphia architecture firm Geddes, Brecher, Qualls, and Cunningham (GBQC) to translate Dilworth’s objectives into an innovative building design. These objectives led to a design that included a curvilinear façade composed of white precast concrete panels; a welcoming front plaza and main entrance facing Franklin Square; a transparent ground floor including public-facing functions such as a central public lobby and elevator core, an auditorium, and a cafeteria open to the public. Police operations were pushed to the sides and upper floors, to the east and west elevator cores. The architecture section discusses the design in more detail.

Unfortunately, the police department took steps that undermined these design concepts. First, the department encircled the building with a concrete wall. This wall imparted a fortress-like appearance to the building, rather than the feeling of openness, welcome, and transparency intended by the mayor and the architects. Second, the police department relocated the main entrance from the front plaza to the rear parking lot. Visitors thus entered through a parking lot of police vehicles rather than the open, welcoming front plaza.

Associations with urban renewal

The Police Administration Building was built adjacent to Franklin Square, between the Old City and Chinatown neighborhoods. At the time of construction, a streetscape of rundown factory lofts, vacant houses, burlesque theaters, cheap hotels, and saloons surrounded the building.

Shortly after completion, the entire area was designated as part of the Independence Mall Urban Renewal Area, with devastating effects on Chinatown in particular. As described by Inga Saffron,

“By the early 70s, virtually every building between Arch and Vine would be leveled … The destruction cut off Chinatown from Franklin Square park, its only patch of green space, and left the city’s ambitious new police headquarters an island, encircled by surface parking lots. More than half a century later, that asphalt wasteland remains, one of the few undeveloped sections in an otherwise revitalized Center City.”

Associations with aggressive policing

Philadelphia has a long history of aggressive, heavy-handed and often racist policing going back to the department’s founding in the early 1800s, at least 150 years before the Roundhouse, according to a 2020 Inquirer investigative report. However, the Roundhouse became a public symbol of a police force which played an outsized, and often controversial, role in the conflicts of the day, be they related to crime, social unrest or even politics. Television news reports used the building’s curving concrete façade on a regular basis as a backdrop for reporting on the latest newsworthy crime, arrest, police scandal, public protest, etc.

Under the leadership of Frank L. Rizzo, first as police commissioner and later as mayor, the Philadelphia Police Department earned a well-documented reputation for brutality, racism, and civil rights abuses. The close association between Rizzo, for years one the most controversial public figures in the nation, and the Roundhouse further complicated the relationship of the public with the building.

The Rizzo era left a police department – and by association the Roundhouse – tarred by a seemingly endless string of scandals and controversies. Examples include the 1967 police assault on student protesters outside the Board of Education, a 1974 report by the Pennsylvania Crime Commission outlining systemic corruption at all levels of the department, a 1977 Pulitzer Prize-winning series in The Inquirer exposing the use of routine violence by police to extract confessions from suspects, and violent clashes with MOVE in 1978 and 1985, the latter resulting in 11 deaths and the destruction of a neighborhood.

“Yet there has been little citywide soul-searching about the racism that infected the police ranks before the Roundhouse was built.”

—Inga Saffron, Inquirer, Jan. 03, 2023

Police Reform

After the 1985 MOVE bombing, Commissioner Kevin Tucker launched a determined effort to remake and modernize the force. He embraced the philosophy of community policing to reestablish trust with Philadelphia’s residents by bringing back foot patrols, opening mini-stations, and providing Spanish language courses for officers. Tucker sent dozens of commanders to management seminars at Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government. “The man came in and literally turned the department around,” said Robert Hurst, who, as head of the police union, often clashed with Tucker.

Over the past thirty-plus years, the police department has embraced reforms, increased its diversity, and been led largely by progressive Commissioners, several African American, including current Commissioner Danielle Outlaw, the first woman to direct the force. Despite periodic setbacks, the police department today enjoys an improved relationship with the residents it serves. Still, it is difficult for some to ignore the memory of the worst the Roundhouse once represented in the minds of many.

Next Up: